A post from last year revisited--

Let's remember what Christopher Columbus was really like:

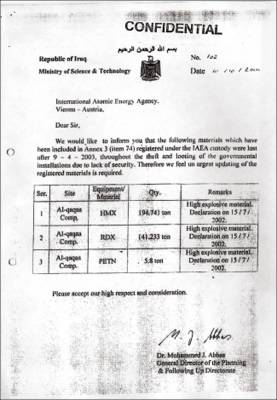

Landing of Columbus stamp, 1893

On his second voyage, at Hispaniola (the large island that is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) Columbus and his men devised a system to extract gold from the native population:

Every man and woman, every boy or girl of fourteen or older, in the province of Cibao (of the imaginary gold fields) had to collect gold for the Spaniards. As their measure, the Spaniards used those same miserable hawk's bells, the little trinkets they had given away so freely when they first came 'as if from Heaven.' Every 3 months, every Indian had to bring to one of the forts a hawk's bell filled with gold dust. The chiefs had to bring in about ten times that amount. In the other provinces of Hispaniola, twenty-five pounds of spun cotton took the place of gold.

Copper tokens were manufactured, and when an Indian had brought his or her tribute to an armed post, he or she received such a token, stamped with the month, to be hung around the neck. With that they were safe for another three months while collecting more gold.

Whoever was caught without a token was killed by having his or her hands cut off. There are old Dutch prints (I saw them in the collection of Bishop Voegeli of Haiti) that show this being done: the Indians stumble away, staring with surprise at their arm stumps pulsing out blood.

There were no gold fields, and thus, once the Indians had handed in whatever they still had in gold ornaments, their only hope was to work all day in the streams, washing out gold dust from the pebbles. It was an impossible task, but those Indians who tried to flee into the mountains were systematically hunted down with dogs and killed, to set an example for the others to keep trying.

Resistance was futile: "It was at this time that the mass suicides began: the Arawaks killed themselves with cassava poison." --from

Columbus: his Enterprise; Exploding the Myth by Hans Koning, based on the reports by Bartolome de las Casas.

Perhaps you think we should not judge Columbus by the standards of today--surely in the light of the 15th century he was a great and noble hero!

Apparently there were plenty of men of that distant and benighted age that criticized Columbus and the Spanish misbehavior in the Americas; among them are Bartolome de las Casas, Antonio de Montesino, Fray Buil, Pedro Margarit, and the Dutch etcher DeBry. So do not believe the lie that plundering, raping and massacring people was somehow considered acceptable behavior in the past. It wasn't.

Even Samuel Eliot Morison, in

Christopher Columbus, Mariner an otherwise quite positive portrayal of the hero Columbus admits that "the cruel policy initiated by Columbus and pursued by his successors resulted in complete genocide."

I have recently been reading

A View of the Causes and Consequences of the American Revolution; in Thirteen Discourses, Preached in North America between the Years 1763 and 1775: with an historical preface by Jonathan Boucher, apparently an Anglican minister that returned to England after the outbreak of the American Revolution. The first sermon, "On the Peace in 1763" includes this reminder of what true greatness is:

True greatness deserves all the honour that the world can pay to it: but, fields dyed with blood are not the scenes in which true greatness is most likely to be found. He who simplifies a mechanical process, who supplies us with a new convenience or comfort, or even he who contrives an elegant superfluity, is, in every proper sense of the phrase, a more useful man than any of those masters in the art of destruction, who, to the shame of the world, have hitherto monopolized almost all its honours.

Amen.

Father, let me dedicate All this year to you

In whatever earthly state You will have me be

Not from sorrow, pain, or care Freedom dare I claim;

This alone shall be my prayer: Glorify Your name.

--from New Year's Hymn by Lawrence Tuttiett, 1864 (alt.)